![]()

![]()

This investigation explores one of the oldest dialects of English in order to discover which features of the language spoken by the Anglo-Saxons remain buried in common use today. Spoken language is analysed on two levels: regional colloquial speech among people who like tractors; and the international standard of English, which we prescribe as good practice for effective communication in a second or other language.

The research is conducted by analysing the characteristics of a variety of East Anglian English, known as Suffolk – taking its name from the county in the east of England where it is spoken. These are compared with Modern Danish, with which the Suffolk dialect shares a common ancestry.

In favour of such a comparison, rather than one with the language spoken by the Anglo-Saxons, ie Old English, is the fact that while the Suffolk dialect and Danish evolved simultaneously, they have done so largely independently of one another – each with a lexis that is unintelligible to the other.

In the 2001 volume East Anglian English by Jacek Fisiak and Peter Trudgill, the point was made that this variety of English has furthermore received little attention from linguistic scholars over the years. This investigation does not pretend to satisfy this need but began simply as a way for me, as researcher, to show off my linguistic knowledge, or lack of.

The findings (foind’ns) nevertheless go some way to demonstrate important points in the evolution of language, proposing that while lexis is the most susceptible to change, phonology is possibly the least. The investigation includes original, empirical findings that someone, somewhere, may find useful in their own study of the origins of English. If that is you, and you have got this far, please remember to kindly add a comment at the end of this piece.

Fank yew

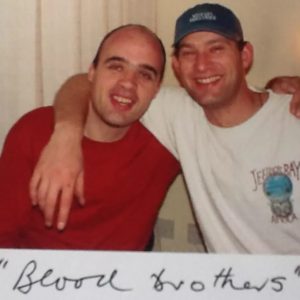

First and foremost, I would like to thank my ‘most Suffolk’ of friends, Jason Taylor-Balls, for his expert consultation and lively exchange of ideas – not just in identifying how something might be said in Suffolk, but also for his cooperation in suggesting a transcription of spoken language. Suffolk, as with many dialects has no current spelling convention. In addition, I would like to thank the community of Bredfield in the 1980s, for their part in my integration to ‘Suffolk ways’.

For the Danish comparison, I thank my family, especially my uncle, Iwan Grundtvig-Madsen for his life lessons and corrections, as well as Professor Hans Basbøll of the University of Southern Denmark, for patiently roofreading this paper and suggesting edits. Credit must also be given to those, such as my brother Nic, who on some very intoxicated occasions, participated in the delight of identifying and assimilating, what can only be described as the phonology of Danish!

Intra'ducsh'n - gett'n digg'n

In this (electronic) paper I will introduce both the Danish and Suffolk tongues, and by identifying their characteristics, attempt to answer which components (eg semantics, syntax and phonology) of Anglo-Saxon speech continue to the present day and contribute significantly to the accepted standards of English, as described by reputable dictionaries.

The Dig, a British film drama released on Netflix in 2021. It tells the story of a historically enlightening archaeological find in the east of England – the Anglo-Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo. Striving for accuracy, the film not only tackles the events of the excavation in the 1930s, but also tries to get things right linguistically, by having its cast perfect the voices of the people it portrays.

Despite the Suffolk Dialect having an undeniable role in the formation of other, much more widely spoken, varieties of English, both the county and the dialect remain surreptitious and with no recognised international significance.

It may be argued that Modern Danish – with just six million speakers, 86% of whom speak English as a foreign language – is not reliable for such an investigation as it has already been influenced considerably by English media and culture, but it is hardly likely that such an influence would have come from the Suffolk dialect. The county of Suffolk has a population of just 760,000, is largely agricultural, and those who move away from the area are often quick to disguise any trace of an accent.

For the purpose of this investigation, Danish shall provide the benchmark, while the focus shall be on the Suffolk dialect.

By pooling on perhaps what has become the largest bank of recordings of any one Suffolk speaker – a puppet fox called Mavis, I will argue that there are significant further traces of the first speakers of English to be unearthed in England’s easternmost county.

Digg'n up Suffolk

‘East Anglia – the remote easternmost area of England – was probably home to the first ever form of language which can be called English…

Jacek Fisiak and Peter Trudgill, Professors

It is very likely that when the early Angles and Saxons first landed on British shores in the 5th and 6th Centuries AD, they would have come through the region today known as Suffolk.

Travelling up rivers – such as the Alde, Deben and Orwell – they would have encountered the indigenous Britons, who spoke an ancient Celtic language, related to Welsh. Together they began trading and the natives were invited to integrate, though there seems to be some dispute about how cordial this invitation was.

The settlers established hām (homes) at Framlingham, Saxmundham and Rendlesham – where someone wrote an epic Anglo-Saxon poem called Beowulf, but which had nothing to do with wolves. The homes became burg (settlements) such as Woodbridge (a man in one of its pubs told me the name had nothing to do with any timber water crossing but was originally Odin/Woden’s burg), Aldeburgh (old burgh), and Burgh (burgh). Elsewhere whole towns were founded – the town, for example, by a man called Ib, who had a creek (-wīc), where people today continue the losing battle in a game called football; and another town in the north, which lay next to a wald (forest) , was appropriately named Southwold.

The medieval migrants came over the sea from mainland Europe, took all the jobs, and stole the women – who, of course, they could not understand then and struggle to do so to this day.

The conditions for sowing their wild oats, despite having no tractors, and establishing a kingdom were ripe.

In homage to the peninsula from where they had set out, they named the new land Anglia – which as many will recognise, also gave its name of a television station – with shows such as Survival, Tales of the Unexpected and Patrick’s Pantry. But this was all still a long time before Netflix discovered the ship burial at Sutton Hoo (Suffolk for something who).

Yngwie Malmsteen – making the same album since 1984.

Because they had come from the Baltic, the Anglo-Saxons spoke a Germanic language that belonged to the group known as North Sea, also called Ingvaeonic (from the sons, and daughters, of Yngvi – a bit like Yngwie Malmsteen, who also can’t spell his name).

This language was spoken from Jutland, the bit of Denmark that juts out of the top of Germany, towards Scania (where the trucks come from) in Southern Sweden, and the very flat and exposed region known as Frisia – where the cows are always cold because they’re Frisian!

One notable feature of the language spoken by these Anglo-Saxons was the lack of any distinction between the singular and plural forms of verbs. This continues in Suffolk today. When speakers of the local dialect report, for example, what someone else has said, their indirect speech will include structures such as I go to him; you go to me; then s/he go to them; and they go to us etc despite the fact that nobody goes anywhere. Purists will be quick to correct them, scoffing at the lack of education and a lack of knowing how to decline their verbs – but perhaps it is actually the speaker that is getting it right and everyone else is getting it wrong.

As the new Anglia (the region, not the TV station) became more popular, people went off in different directions. Some folk stayed in the south, and being adept linguists named their region (in their best pronunciation) to honour this fact, Suffolk.

The less fortunate north folk, however, spoke differently, but unable to come up with anything more original named their county similarly, Norfolk.

As a new language began to take shape, these same linguistically astute speakers called it Ænglisc or Anglisc or Englisc (spelling was definitely not a thing back then). Influenced by this migration, the language blended to adopt new colloquialisms. Among its bravest and most fearless speakers were those who went to the distant foreign lands of the Middle Earth, or Midlands, such as Lincolnshire or Lindsay, and Bedford (where the trucks come from). Strange new dialects were formed in its wake, until it reached Hull and surrendered.

It was there that the norsemen, who coincidentally had arrived from the north, conquering the celtic speaking Britons as they went, first encountered others, who spoke a very similar language that everyone could relate to, and not at all like Welsh.

In 1066, the Normans, other northerners who had taken a detour through France and adopted a je ne sais quoi, crossed the vast ocean of the English Channel. Upon their arrival on the island of the Britains (except it wasn’t) they began introducing everyone to French. But English had already become so deeply ingrained in everyday speech that the only hope French stood was with a whole bunch of fancy legalese and jargon that nobody used anyway – and so it remains to this day.

For the next couple of hundred years and a bit, the dialects of East Anglia carried on quietly, maintaining many of the features of the mother language. Dialects which were spoken by decent country folk who had little else to do than breed like rabbits, they developed and mutated.

When centuries later, the going got tough in the old world, many set off to make new lives for themselves in a new one, but not forgetting to take their language with them and setting the ground for

further linguistic migration. Evidence of this can easily be found today by looking at a map of the Americas and Australiasia and counting the number of familiar place names – Ipswiches and Sudburys (-ies?), but perhaps, for obvious reasons, not any Leistons or Halesworths.

Speakers of accents such as the Hoi Toider (High Tider) dialect of American English, for example, need not turn over many stones in Suffolk to find out where their unusual dipthong [ɔɪ] came from.

Today, as a consequence, Suffolk speakers who do go ‘abroad’ (anywhere beyond the county borders) are often mistaken for Australians, who according to dialect specialist and entertainer Charlie Haylock, are simply speaking Suffolk with their mouths ‘wide open’. This comes as no surprise to anyone who knows Australians.

‘Meanwhoile’, says Charlie, those who try to imitate Suffolk pronunciation, all too often end up sounding like ‘West Country pirates’, perhaps earning them the same amount of respect as Dick van Dyke for his ‘jolly ‘oliday with Maaary’, or for that matter, any Briton trying to speak ‘merican.

The producers of The Dig were clearly aware of the repercussions of having their cast sound too educated and took no chances. Ralph Fiennes for one, employed Charlie as his voice coach.

Taking Suffolk’s history into account, it seems plausible, its dialect is indeed one of the first of all dialects of English.

And as speakers of the Suffolk dialect will insist: if all that was left as evid’nce of the first Anglian settlers was ‘a brooken helmet ‘n’ a bit of rotten ol’ wood, et would be a bit rum, wouln’t et’?

Digg'n up Danish

‘We may have a well-founded opinion about whether our mother tongue is of the tribe to which we belong – Danish is simply corrupt Icelandic – or some nonsensical hotchpotch of Norse and Low German’

NFS Grundtvig – philosopher, historian, distant relation

It may come as a surprise to some that Denmark, the tiny land that gave us Google Maps, Lego, and the best lager in the world, probably, also has its own language. Although influenced by both German and English, it is neither. Instead it has bold beginnings in the times of the Vikings.

But, even when England was overrun almost entirely by Danes, in an area known as Danelaw (Danish rules UK), by speakers of what’s known as the Danish tongue (dǫnsk tunga) it really wasn’t! The language spoken by those Danes was Norse. Mutually intelligible between its speakers, as they ‘negotiated’ with the flower-pressing, poetry loving monks of Lindisfarne, their language was already starting to fracture at its core.

The western variety of Norse clung to double vowel sounds – ei, au and the like; but a rebelious eastern variety, took a fashionable jump to the left with a vowel shift (Monophthongization, for show offs) changing bein to ben (bone), heim to hem (home), and brauð to brød (bread).

The successors of these two varieties of Norse are today sometimes referred to as insular – which is in no way a reflection of the IQ of their speakers, but a reference to the fact that the languages are spoken in islands such as Iceland and the Faroes – and continental Scandinavian, which has nothing to do with croissants.

The latter, ie. Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian Bokmål (a Koiné, which is not Suffolk for a round piece of metal money, but a combination of several varieties of the same language). These languages fortunately remain so close to one another that makers of TV dramas set in the Scandinavia don’t have to bother with such trivialities as language.

The similarity between words of Norse origin and those found in English today, is not surprising when one considers that while the medieval Scandinavian tourists were still on equal terms with their British hosts – or as the Normans later called it au pair – they helping the Britons’ with their everyday needs, and participating in good housekeeping. Subsequently left behind a rich vocabulary of familiar words to remember them by – berserk, club, ransack, scathe and slaughter – as well as place names across the country: –by meaning settlement (e.g. Whitby, Grimsby…), -ey meaning island (e.g. Butley, Otley…) and kirk meaning church (e.g. Douglas, Captain…).

Until the end of the Vikings’ welcome in England, the language we today call Danish would have been but a twinkle in the eye of those who claimed to speak it.

After those Danes left about a thousand years ago, English was left to eveolve using its own devices. To be able to discuss abstract themes at a time of enlightenment in the sciences and arts, philosophy and literature, for example, words were borrowed, with no intention of ever giving them back – from French and Latin, as well as the spoils of conquests of other lands (eg bananas in pyjamas, Las Hijas de Ketchup and alphabetti spaghetti).

This was, of course also true in the Kingdom of Denmark. Having been sent back to where they came from, with long faces on long ships, the lives of the Danes turned soft and flaky – much like the pastry with which the language shares its name.

Resigned to centuries of fishing for small aquatic crustaceans, and farming pigs, while making room for a new god, new terms also had to be found.

The Danes ‘borrowed’ their words from the Germans.

In the Middle Ages Denmark became an important hub for trading in medieval goods – not the retro costume and wigs, Lord of the Rings swords, that we know today, but prawns!

Sandwiched between the Scandinavian peninsula and the lands to the south, there was a rising need to allow free trade as well as defend the borderlands, including the same corner of land which gave its name to the land across the North Sea.

A commercial league, or Hanse took shape and soon everyone who was anyone wanted to be a part of it. Before the people of Old Anglia could say ‘Friedrich zu Solms-Rödelheim’, their language had struck once more – this time as the lingua franca of business across Northern Europe, and as a rival to Latin.

Middle Low German, as it came to be known, was no indication of how deep down in the vocal tract it was spoken. In fact, nobody today seems to be able to agree if this language (also known as Middle Saxon and believed to have been spoken from around 1100 to 1600) and if its vocabulary – where, for example, a butterfly is a botterlicker – was ever a language in the first place, or just someone having a bit of a laugh.

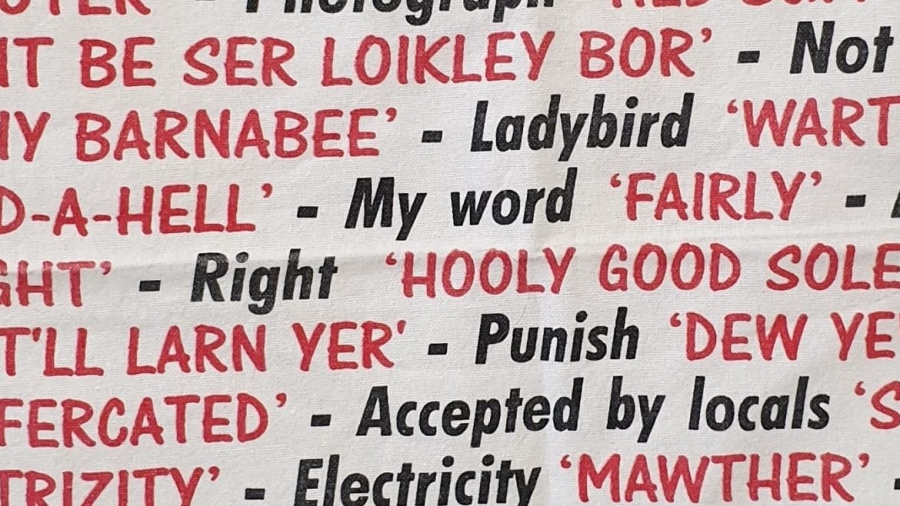

This seems especially to be the case in the areas where its present day descendant, Low German (or plattdütsch), can be heard on the radio in news broadcasts, or in plays by provincial amateur dramatic societies, and its vocabulary is archived on novelty tea towels and novelty ceramic mugs – a fate that also befits the Suffolk dialect. What we can know, however, is that Low German is the closest language (or not) to English, which is not at all to be laughed at.

At the height of Hanseatic power, low German too, had an important influence on the Continental Scandinavian languages, changing Danish to its modern day likeness to what is cruelly diagnosed by its closest neighbours being an illness of the throat.

By loading the video, you agree to YouTube's privacy policy.

Learn more

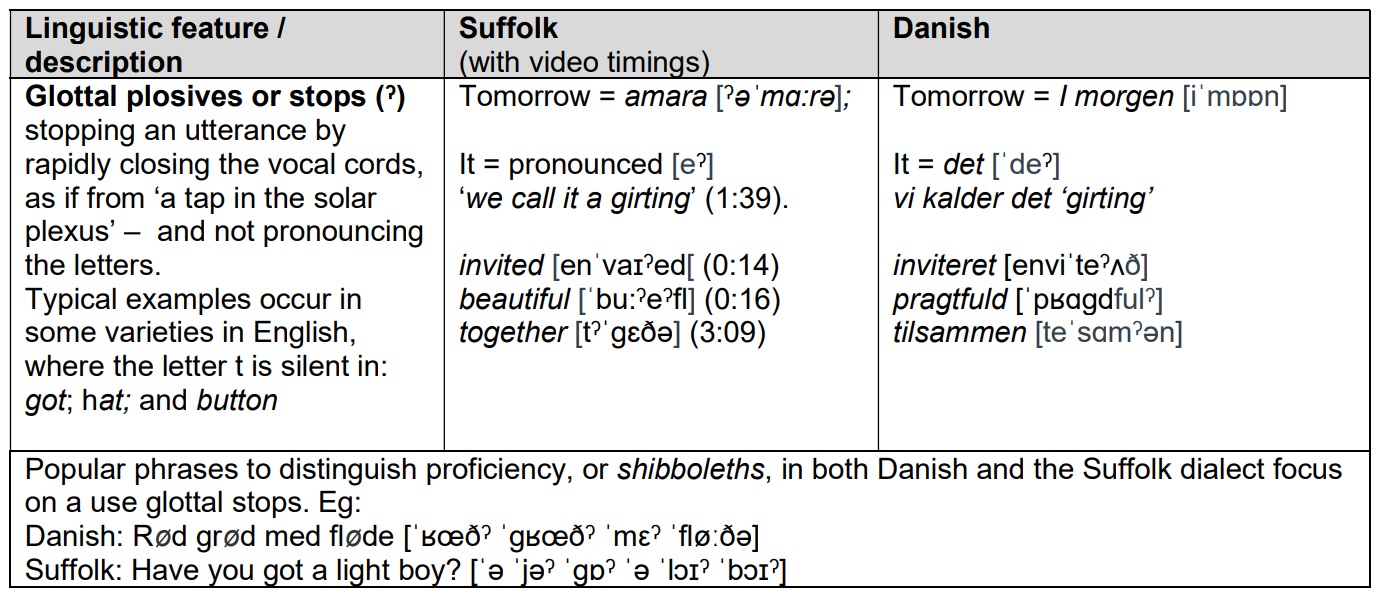

The reason for this unkind stereotype of Danish is perhaps its obvious penchant for glottal plosives or stops, described by Suffolk speaker Jason Taylor-Balls as like ‘one was about to make the t sound but someone decided to tap you in the solar plexus’.

Perhaps here, we may also begin with our comparison with the Suffolk dialect. Just as the Danish town of Sønderborg [ˈsønˀʌbɒˀw], for example, has a silent d, both rs and a g, the Suffolk pronunciation of Aldeburgh [ˈɔːlbrə] rudely ignores the de, u and gh, and, it has been observed, in the nearby town of Leiston, every letter with the exception of the ur.

In a further comparison to the Suffolk dialect, Danish has also been siad to be ungentle to the ears of its hearers. As early as 1554 Hemming Gadh, a Swedish bishop, noted that the Danes do not ‘stoop to speak like other people, but press the words forward as if they will cough, and appear partly to deliberately turn the words around in the throat, before they come forward…’.

Gadh was among the first to notice an almost unique feature, known as the stød (meaning shock or jolt), which has since been described by Professor Hans Basbøll as ‘the most Danish of Danish things’.

The stød is not quite the same as a glottal stop, but is perhaps a remnant of that Norse vowel shift all those years before. Best described as a single vowel that has two separate but very short syllables, which may be, or sound like, glottal stops – the phrase hej mor [ˈhɑj ˈmoɐ̯] meaning ‘hello mother’ will to everyone else sound no different to hajmord [ˈhɑjˀmoˀɐ̯] ‘shark murder’, which while opening up wonderful possibilities for further TV crime scenarios, to the Danes remain as disimilar as their English equivalents.

Another way to explain the stød might be to compare this essential linguistic feature to the vowel sounds in the Suffolk pronunciation of water [ˈwɔːˀə] or matter [ˈmæˀə], or anyone else, for that matter, saying those words when stepping barefoot on another very Danish of things, the lego brick.

Mavis-olagy

This investigation consisted of watching the same video – by a puppet fox called Mavis – again and again, and again. Each time transcribing the common features of Suffolk phonology, so that these could then be compared to similar examples in Danish, using my own knowledge of the language.

The 3:32 minute video, Mavis at Snape Maltings, was posted on Sep 16, 2017 on the Suffolk Fox Youtube channel. The channel currently has about 70 videos, and 275 subscribers, and consists mainly of Mavis’ reports on events in the region, in a BBC Radio Suffolk series called During the virus.

Suffolk Fox is not only the most up to date, but arguably also the largest bank of recordings of any one Suffolk speaker. This makes it an invaluable resource for any study into how the county speaks. It is perhaps important to question here whether Mavis is simply speaking with a Suffolk accent, i.e. pronouncing her words as they would typically be said in Suffolk, or speaking the dialect. The latter would necessitate an inclusion of regional grammatical structures, Mavis clearly follows the dialectal verb declension (e.g. who write all them Suffolk books; Off she go) for example, and vocabulary, of which there are no examples in this particular video. While dwile-flonking, and girting are East Anglian, they are not exclusive to Suffolk.

In order to identify traces of the language of the Anglo-Saxons, however, the focus is chiefly on phonology. As the sounds of speech exist in both accent and dialect, the video is nevertheless appropriate for the purpose of this study.

It should perhaps also be noted that such investigation will turn an otherwise delightful video into re-run overkill, and is likely to cast rather a doubt upon the sanity of the researcher, who many would hope has better things to do, during the virus.

Foind'ns

This investigation shows that while there are similarities in the lexis and syntax of the Suffolk Dialect and Danish, they are clearly distinct:

- While many words are very similar in both tongues, they are not exclusive and also exist in other varieties of English, and/or other Scandinavian/Germanic languages.

- Nouns that are considered unique to the Suffolk dialect and Danish often share a common heritage – a ladybird/bug, for example, in the Suffolk dialect is a Bishee Barnabee: and in Danish mariehøne (lit. Mary hen). All three words refer to the similarity between the insect’s little red cloak, and one typically worn by religious figures, from the mother of Jesus to a bishop, in medieval paintings. These words are not understood by speakers of the other, nor are their associations exclusively Germanic.

The Russians for example, call their ladybirds is Божьи коровки (God’s cow), which makes perfect sense. - In the Suffolk dialect, it is common for ‘that’ to replace ‘it’. In Mavis’ video, for example, she says: ‘they say that’s going‘ (0:28) and ‘see how that come out‘ (0:53).

In Danish there is no distinction between the two words – i.e. the third person singular pronouns det and den, are also used to indicate ‘that’ as a pronoun and determiner, but also as articles. - In the Suffolk dialect verbs rarely conjugate in the present simple.

In her video, Mavis says: ‘Charlie Haylock, who write all them Suffolk books‘ (1:21) and ‘Off she go‘ (2:29).

Danish verbs do not vary according to person or number. E.g. jeg/du/han/hun skriver – I/you/he/she write(s); jeg/du/han/hun går – I/you/he/she write go(s).

There is no doubt that the Suffolk Dialect, as a variety of English, and the Danish language belong to the same family, but there seems to be insufficient evidence in the above to see how they have been considerably influenced by the same language. For that, we need to look at phonology.

By loading the video, you agree to YouTube's privacy policy.

Learn more

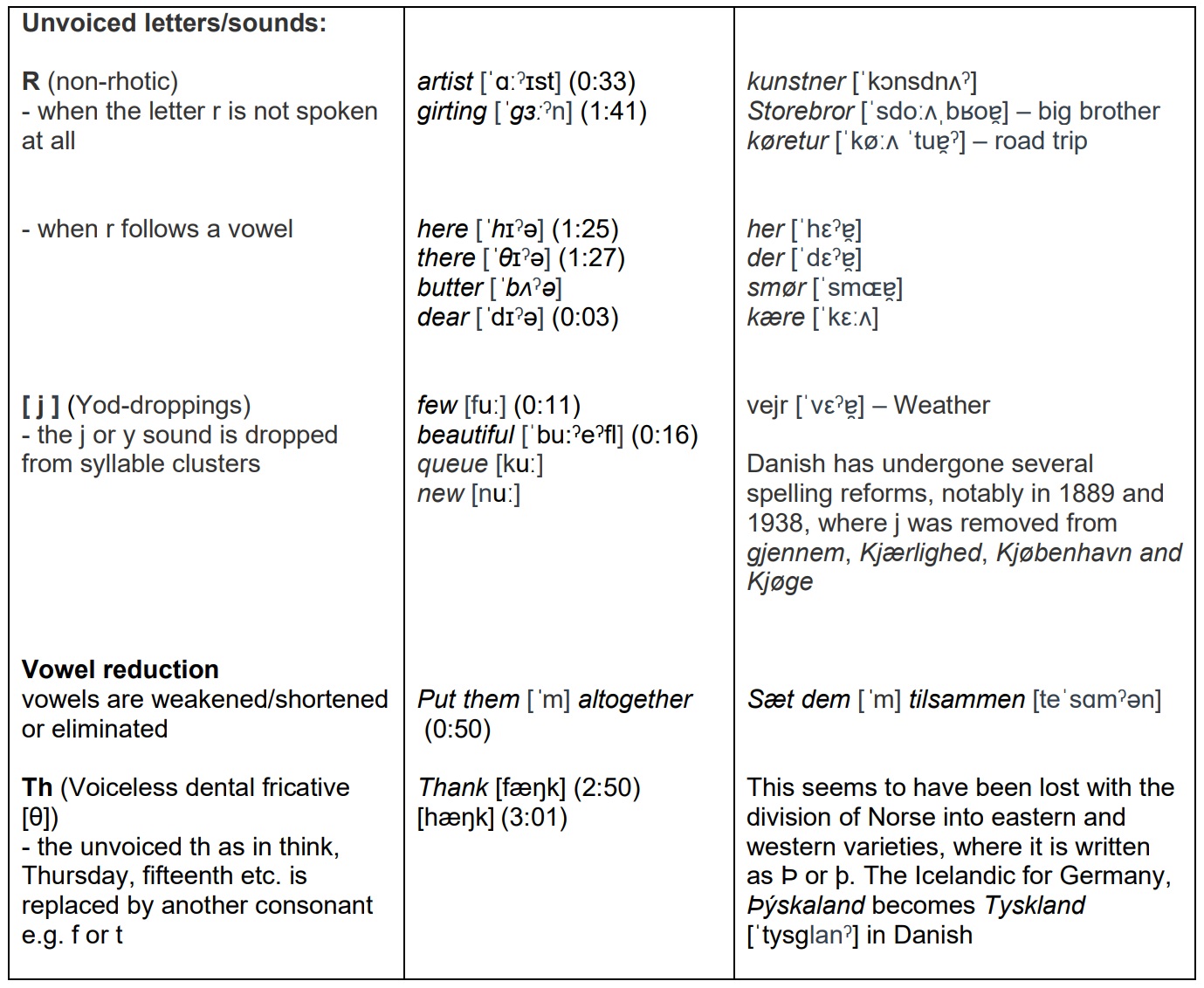

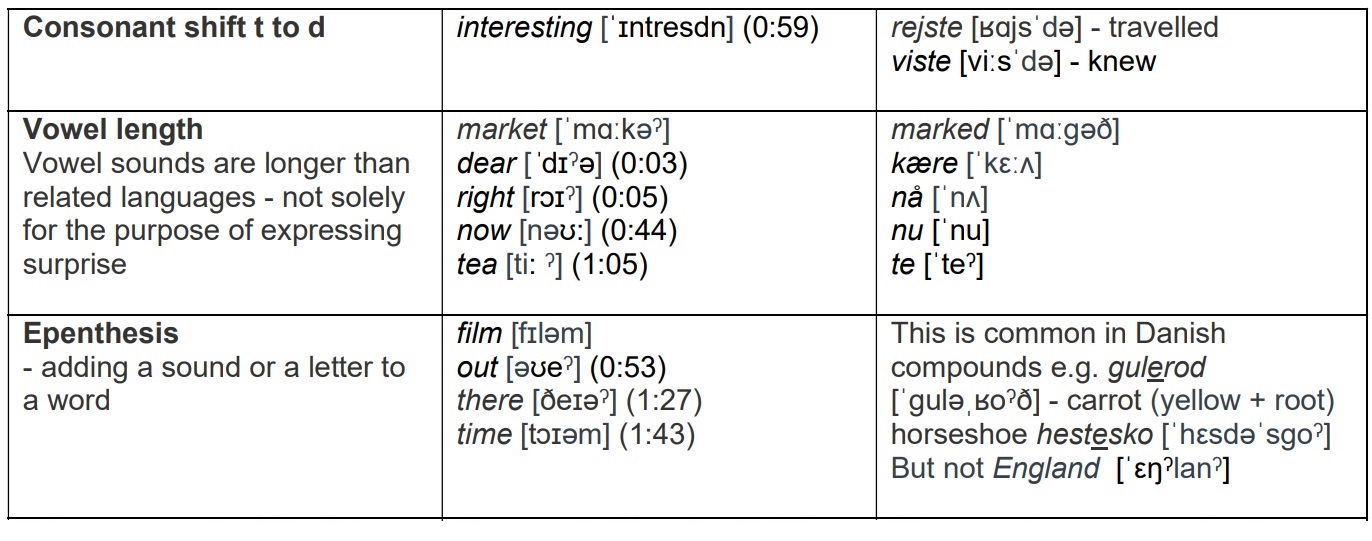

The below table compares the phrases heard in Mavis’ video, above, with their Danish translations.

The Old Anglian influence on Danish occurred after Suffolk and Denmark went their separate ways, and would subsequently would have been more recent. I have not compared typical features of Modern Danish with the Suffolk Dialect, with the exception of the stød, which I have questioned whether there is evidence of this in the Suffolk dialect.

There may be evidence of the stød in the vowel length mentioned in the above table. When reflecting on the Suffolk pronunciation of the two words floor and door, there seems to be a subtle difference in the oo phoneme between the two, as with the single o in for or more andThor – while the former is monosyllabic, the latter is disyllabic.

It is therefore my belief that this is evidence of the stød, suggesting it is much older than when it was first recorded in 1743.

Cunclooshen

In this investigation, I have focussed wholly on the Suffolk Dialect, with a blatant disregard of how its features also occur in other varieties of English. In Britain, no-one has yet been able to explain, for example, why the Anglo-Saxons also chose to live and leave their geographical observations in place names elsewhere – such as Essex (easy sex) and Middlesex (about average). In addition, in other regions such as the Scottish lowlands, where the language of enlightenment was not necessary, there was a significantly lesser influence of French and Latin.

The features I have studied may also be found in the standard pronunciations described by today’s dictionaries of British (e.g. Oxford), American (e.g. Merriam Webster) and Australian (e.g. McQuarie) English, and cannot be claimed by the Suffolk dialect alone. These include:

- Yod droppings: eg dukes [ˈdjuːks] new [ˈnuː] and Tuesday [ˈtuːzdeɪ] or [ˈtuːzdi] (Merriam Webster)

- Glottalisation: stopping, e.g. the [ˈt͟hə] of [ˈə] (Merriam Webster) burglar [ˈbɜːɡlə] (Oxford); and flapping about, referring not to the speaker running about like a headless chicken, but to how a [t] may sound like a rapid [d] in words like metal [ˈmetl] or partner [ˈpɑːrtnər](Merriam Webster) – in Suffolk the [t] is lost entirely, as it is in Australian [ˈpatnə] (McQuarie)

- Rhoticity: eg hazard [ˈha-zərd]; rather [ˈrɑːðə]; murder [ˈmɜːdə] and remark [ˈrɪˈmɑːk] (Merriam Webster)

Without an awareness of the above, for example, The Dukes of Hazard would just not sound right. It is this that will help anyone trying to imitate accents and dialects, such as the cast of The Dig, to get things right.

It is also important to mention here that the features I have described in this investigation are by no means exclusive to the languages I have described, or even the Germanic family of languages – non-rhoticity, for example, apparently, also occurs in the standard dialects of Malay.

As for the evolution of language, the findings of this investigation make it is easy to jump to the conclusion that phonology must be the language component that is least prone to change. I have, for example, demonstrated how some common phonological features can be identified in the languages and dialects which have evolved from Anglo-Saxon and that lexis has changed, to a point that Old English sounds as foreign to speakers of Modern English as Icelandic. Vowel shifts, such as the one that divided Norse into two varieties, or the more recent one in English, that allowed us to argue whether route rhymes with boot or out, can occur like volcanic eruptions, quite suddenly in the great scheme of things and without warning.

The Great Vowel Shift in English was first identified and studied by Otto Jespersen (1860–1943), who besides being a linguist and teacher, was coincidentally a Dane! And as we again mention Danish things, it may be the case that the stød is nothing more than an early glow of the next eruption – a simplification of vowels which were previously separate, such as in Norse. Such a stodisation, leading to the birth of dipthongs and tripthongs, i.e. words which include several vowel sounds: hour [ˈaʊə], fire [ˈfaɪə], but perhaps not Penelope Pitstop’s tetraphthong ‘help’ [ˈhæeɪɛlp].

It is important to note that this investigation does not show whether the proportion of speech sounds that remain is greater or even comparable to the proportion of words that remain little changed – the word axe for example, as a tool used for chopping wood, is believed to originate from the Proto-Indo-European heḱ, meaning sharp, pointed and is in Low German ex, Danish it is økse, Icelandic öxi, Old English æx, and Latin ascia – which might not work quite so well as a name for an underarm deodorant.

Finally, while an investigation such as this may be interesting to shed light on how we spoke in the area known as the dark ages, it may ultimately be more useful to identify which features of our language have stayed the course, and provide an illuminated path to the features of future speech. For such a comparison we must do a bit more digging.

Bibl'ogruphy

Fisiak, J. & Trudgill, P. East Anglian English D.S. Brewer 2001

Skeat, W. Place-names of Suffolk Cambridge Antiquarian Society 1913

Culpeper, J. History of English Third Edtn Routledge 2015

Grundtvig, N F S, Danske Samfund 1839

(Translation of the original: ‘vi kan have nogen vel- grundet Mening om, enten vort Modersmaal er den Folkestamme, vi tilhøre, eiendommeligt, eller Dansk blot er fordærvet Islandsk, eller et Pluddervælsk og Kiørsammen af Nordisk og Plattydsk’)

https://sproget.dk/

https://dialekt.ku.dk/

Basbøll, H, The Phonology of Danish (The Phonology of the World’s Languages) Oxford University Press 2005

Examples given by J. Taylor-Balls (personal communication, February 2001)

https://tophonetics.com/

https://www.oed.com/

https://www.merriam-webster.com/

https://www.macquariedictionary.com.au/

https://www.etymonline.com/

As a barely peripheral aside, Suffolk’s Haverhill is the of the Massachusetts city Haverhill, renamed in honor of political figure and major landholder Nathaniel Ward, born in Haverhill, Suffolk. His son was John Ward, the colony’s first minister.

The local Suffolk accent (still spoken by the town’s older residents and certain fox puppets) has largely been replaced by a London accent. The impact of this is notable because the traditional Suffolk pronunciation of the town was HAYvril, (as Massachusetts still pronounces it), but as Haverhill Suffolk increasingly becomes a “London overspill” town, the Suffolk dialect has been diluted by a hybrid of London, Suffolk and Essex. So, in the original Haverhill, it is now more commonly pronounced ‘Hay-ver-hill.’